95% of cyber security breaches are due to human error[1]. It could be you. The best bit? You probably won’t even know you’re doing something wrong. You have inadvertently just become an unintentional insider threat.

What’s an unintentional insider threat?

A person becomes an unintentional insider threat when they unwittingly allow a cyber attacker to achieve their goal – whether that’s a data breach, access to systems, or diverting payments to a criminal’s account. This can be through negligence or lack of knowledge, but can also be a result of just doing your everyday job.

Unintentional insider threats are particularly dangerous because the traditional methods of identifying insider threats don’t work – they don’t try to hide emails or files, because as far as they’re aware, they’re not doing anything wrong. If an attacker presents themselves as a legitimate person with the right credentials to request a change, the unsuspecting employee will probably respond exactly as the attacker was hoping.

Trusted employees have access to company-sensitive information, assets, and intellectual property; as well as permission to make financial transactions – often without requiring any further approval. Threat actors target these privileged, trusted people – impersonating suppliers, regulators, and known colleagues – and try to encourage them to do something they have permission to do, but shouldn’t.

“Staff authorised to access sensitive information, manage financial assets, or administer IT systems will be of greater interest to an attacker (and may be the target of a sophisticated spear phishing campaign)." [2]

Why are these threats so prevalent?

Email allows threat actors to communicate with users with almost no defensive barriers between them. Even the most diligent employee gets distracted, rushed, or slightly too tired, which is all it takes for a malicious email to achieve its objective – whether that’s clicking a link, opening an attachment, or trusting the email’s source enough to reply. You don’t expect to be attacked in your safe office environment – threat actors prey on this perceived safety, to catch you off your guard and socially engineer you into doing something you shouldn’t.

Payment diversion fraud is a well-known method of attack, where adversaries pose convincingly as an existing supplier, and request your trusted, authorised employee to change their payment details due to a security incident, or other such urgent, yet credible, situation. This type of fraud doesn’t always happen over email either – phone calls, letters, and even faxes can be used by attackers, in an attempt to avoid detection.

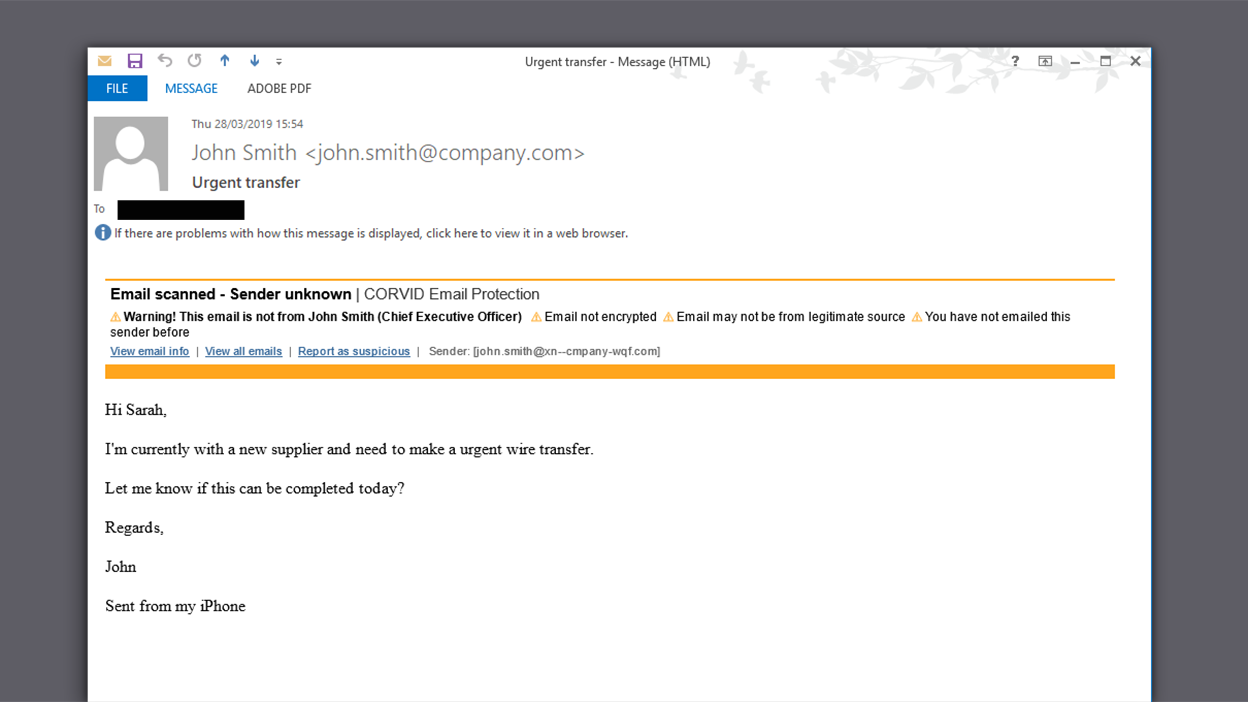

We all know what a spam email looks like, but 97% of people are unable to identify a sophisticated phishing email[3]. This is hardly surprising when you consider that there are, comparatively, so few highly-convincing fake emails – because you don’t see them every day, you’re not always looking out for them. Then there are some methods of impersonation you can’t realistically be expected to detect – for example, spotting the difference between a 1, l, and I (1, L, and i, respectively). Attackers know you’re not meticulously scanning every email for tiny details like this, so they take advantage. Read our blog post on CEO fraud, which covers impersonation like this in more depth. If your email security currently relies on users correctly identifying malicious emails 100% of the time, your defences are going to succumb to attack.

But how can you prevent the unintended?

90% of organisations feel vulnerable to insider attacks[4]. Monitoring normal access and behaviour patterns can give early warning signs of potential intentionally malicious activity, but the same can’t be said for unintentional insider threats. The attacker’s request could be comfortably within the scope of your daily duties.

The information available to users is often insufficient for them to determine whether an email is legitimate. As such, you should be suspicious and challenge requests, especially if they’re unexpected or urgent. Checks should also be put in place for a second pair of eyes to confirm certain requests before any action is taken, for example, changing payment details or making unscheduled wire transfers. If the request is for a financial transaction or asks for sensitive or personal information, phone the person who made the request (or better still, speak to them face-to-face) to confirm it’s genuine.

If you’re ever in doubt, following best cyber security practice is always a good place to start. But there’s only so much humans can do…

PERNIX scans every inbound email to detect what humans can’t. Our clear traffic light banner provides the information you need to make an informed decision about an email’s nature and legitimacy before acting on it, making it easy to avoid becoming yet another unintentional insider threat.

Ready to address your email security? Speak to an expert

Phishing attacks are the most common cause of unintentional insider threats, and have been one of the top methods of cyber attack for the last eight years[5] – it’s time to take a more proactive and technological approach to your email defence. PERNIX is simple to install and provides immediate protection, without costly or complicated setup. Curious about the difference it can make? Get in touch with our experts to find out.

Footnotes

More CORVID blog posts

What Is Managed Detection and Response (MDR)?

In today’s rapidly evolving cyber threat landscape, organisations need more than just conventional security measures. Introducing Managed Detection and Response (MDR) – a transformative solution to cybersecurity.

Managed Detection and Response (MDR): An Overview

Managed Detection and Response (MDR) is a cybersecurity service that combines advanced technology with expert human analysis to identify, investigate, and respond to threats in real time. Unlike traditional security solutions that may only alert you to potential threats, MDR actively works to neutralise them, offering a comprehensive approach to threat management.

The Role of AI in MDR

AI algorithms process vast amounts of data at incredible speeds, identifying patterns and anomalies that human analysts might miss. This not only improves threat detection rates but also reduces the time it takes to respond to incidents.

By integrating AI with human expertise, MDR providers can deliver more accurate and efficient security solutions. AI-driven automation handles routine tasks, allowing human analysts to focus on complex threat analysis and strategic decision-making. This synergy between AI and human intelligence ensures a robust defence against evolving cyber threats.

Key Features of MDR:

- 24/7 Threat Monitoring: Continuous surveillance of your network to detect and address threats as they occur.

- Advanced Threat Detection: Utilises AI and machine learning to identify sophisticated threats that traditional methods might miss.

- Rapid Response: Immediate action to mitigate risks and neutralise threats.

- Expert Analysis: Access to a team of cybersecurity professionals who analyse threats and provide actionable insights.

Types of Threats MDR Effectively Addresses:

- Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs): MDR's proactive threat-hunting capabilities are well-suited to detect and respond to APTs, which can often evade traditional security measures.

- Zero-Day Exploits: MDR's use of advanced technology, such as AI and machine learning, allows for the rapid detection and response to zero-day exploits, offering a crucial defence against unknown vulnerabilities.

- Insider Threats: Continuous monitoring can effectively identify unusual activities within the network, making it an invaluable tool in protecting against insider threats.

- Ransomware and Malware: 24/7 monitoring and rapid response can significantly reduce the impact of ransomware and malware attacks by detecting and neutralising them before they can cause widespread damage.

- Phishing and Social Engineering: The combination of technology and human analysis can detect sophisticated phishing attempts and social engineering tactics, providing a critical layer of defence against these common attack vectors.

- Data Exfiltration: Detection and response to attempts to steal or leak sensitive data, helping to maintain data integrity and safeguarding against data breaches.

What Do MDR Services Offer?

MDR services typically include:

- Threat Detection and Incident Response: Proactive identification and reaction to threats.

- Security Monitoring and Management: Continuous oversight of your security infrastructure.

- Threat Intelligence: Insights and data on emerging threats and vulnerabilities.

- Compliance Management: Ensuring adherence to regulatory requirements.

- Managed Endpoint Detection: Monitoring and protection of endpoint devices.

Benefits of MDR for Organisations

Enhanced Threat Detection:

- Faster response times to security incidents.

- Improved identification of complex and sophisticated threats.

24/7 Monitoring:

- Continuous protection around the clock.

- Peace of mind knowing your infrastructure is always secure.

Cost Reduction:

- Lower operational costs by outsourcing security functions.

- Avoid the expenses of hiring and training in-house security experts.

Access to Expertise:

- Leverage the skills of seasoned cybersecurity professionals.

- Benefit from advanced knowledge and industry best practices.

- Better control over security postures.

- Assistance in meeting compliance requirements.

- Proactive defence strategies.

- Greater insight into network and endpoint security.

Risk Mitigation:

- Preparedness against emerging threats.

- Reduced likelihood of costly data breaches.

How Does MDR Compare to Other Security Solutions?

- MDR vs. Managed Security Services (MSSP): An MSSP focuses on overall IT security management, including implementing new systems and policy adjustments, while MDR specialises in threat detection and incident response.

- MDR vs. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR): EDR tools focus on monitoring and analysing endpoint devices. MDR, on the other hand, offers a comprehensive service that includes EDR along with proactive threat hunting and response.

- MDR vs. Extended Detection and Response (XDR): XDR extends EDR's capabilities to the broader IT ecosystem. MDR does a similar job by providing detection and producing human-led responses to threats.

Integration of MDR with In-House Security Teams

Integrating MDR services with your internal security team can enhance your organisation’s cybersecurity stance. This collaborative approach combines MDR's proactive capabilities with the contextual expertise of your in-house team, leading to increased resilience and effectiveness.

Key Considerations When Choosing an MDR Provider

- Industry Experience: Look for providers with expertise in your specific industry.

- Certifications: Ensure providers have certified security specialists with credentials like CISSP, CEH, and CISM.

- Technology Integration: Verify that the provider’s technology can seamlessly integrate with your existing systems.

- Service Flexibility: Assess the scalability and customisation options available.

- Threat Intelligence Capabilities: Evaluate the provider’s ability to offer comprehensive and actionable threat intelligence.

- Response Times: Consider the provider’s track record for rapid threat response.

Transitioning to MDR Services

- Evaluate Security Posture: Conduct a gap analysis to identify vulnerabilities and prioritise threat areas.

- Set Objectives: Define clear goals for what you want to achieve with MDR services.

- Choose the Right Provider: Select a provider that aligns with your security needs and organisational goals.

- Integration with Existing Systems: Plan for seamless integration with current security infrastructure.

- Change Management: Prepare for changes in operational workflows and provide training for in-house teams.

- Privacy and Compliance: Establish agreements to ensure privacy and meet regulatory requirements.

- Measure Effectiveness: Establish KPIs and metrics to gauge the effectiveness and ROI of MDR services.

Conclusion

MDR services provide a proactive approach to cybersecurity that combines advanced technology with expert human analysis. By utilising MDR, organisations can benefit from enhanced threat detection, round-the-clock monitoring, cost reduction, access to expertise, regulatory compliance assistance, increased visibility, and risk mitigation.

When choosing an MDR provider, it is important to consider their industry experience, certifications, technology integration capabilities, and service flexibility. Integrating MDR with in-house security teams can further enhance protection against adversaries.

Get Started with CORVID's MDR Service

Ready to get started with CORVID MDR? CORVID offers state-of-the-art MDR services designed to protect your business from emerging threats. By integrating CORVID's MDR services, you will not only boost your cybersecurity defences but also gain a strategic advantage in navigating today's complex threat landscape. Don't wait until it's too late—secure your business now!

Contact us to learn more and take the first step towards a safer, more secure future. Get started today and experience the peace of mind that comes with knowing your security is in expert hands.

Cyber Incident Response for decision-makers

It is not unusual for an organisation to have a cybersecurity incident. It may be discovered through internal security controls (such as Anti-Virus, or a Security Operations Centre) , or it may be that a third-party notifies the organisation of an event.

When an organisation becomes aware of an incident it creates a chain of events that benefit from good decision-making. Most Boards are advised that they need to rehearse and prepare for a cyber incident. This can help. However, the majority of incidents do not need, or benefit from, Board-level oversight.

Whilst the decision-maker of an organisation is rarely a cyber-expert: they can play a critical role in achieving an optimum outcome. The following five-points are provided as a guide to the decision-maker.

1. Appoint the right leadership for the incident.

Incident response is a specialised field within the specialised subject of cybersecurity. The majority of people that work in IT or IT security (cybersecurity) have no experience overseeing a security incident. They may have a policy or strategy background and, whilst they may know the theory of how to respond to an incident, have very little hands-on experience.

The first decision that needs to be made is regarding the incident leadership. It may be that an in-house IT or InfoSec lead is exactly the right person to take-charge. If there is uncertainty that a suitable internal person can carry the responsibility the options are to bring in:

- a suitably experienced person to act as a mentor and guide to the in-house lead,

- an external specialist company to support the in-house lead,

- an external specialist company to take-over incident management.

It can be difficult for non-expert decision-makers to gauge whether an internal person is the suitable leader for the incident. Watch-out for the following warning signs that someone may be out of their depth:

- They are trying to apportion blame before the incident is remediated.

- They are using more jargon than usual and it’s hard to understand all the points they are making.

- Terms like “best practice” are used to justify an activity as opposed to an explanation.

The organisation must have confidence that the right expert is leading the response activity. But scared people rarely make the best-decisions. So even if the right person is on-point: they will probably benefit from some reassurance.

2. Set the communication tempo that is needed and try to stick to it.

Whilst it is tempting to want to know everything, every step of the way, this is rarely the most productive way of dealing with the matter. Minimising the communication burden can help maintain the focus on remediating the issue rather than communicating the issue. It is helpful to explain the tempo of communication updates or triggers that necessitate an additional briefing and then encourage the incident responders to get on with the job in-hand.

3. Agree the desired outcomes at the start.

Unfocussed incident response can quickly spiral into a mess. Set realistic outcomes such as:

- Contain the incident to as few hosts and users as possible: this helps recovery and reduces impact,

- Minimise downtime for the organisation and users: this helps maintain business as usual,

- Reduce the likelihood of this impacting other organisations: this helps protect reputation,

- Identify how the attack occurred: this helps prevent future incidents,

- Identify which files have been compromised (exfiltrated, changed, deleted): this helps comply with legal requirements of reporting and assess the longer-term business impact. This is critical.

Setting the priorities at the start helps direct the response. As more information is discovered the priorities may change. But when an incident takes on a life of its own it can be more damaging than necessary.

4. Forensic images are almost never necessary.

The main benefit of a forensic image is if there is a likelihood that there will be a court case at some point and evidence needs to be presented in such a way that it can withstand challenge.

The percentage of court-cases that result from a cybersecurity incident is very close to zero. The cost of capturing, recording and processing computers to a forensic-level is non-trivial. It will cause significant downtime, delay the determination of the impact to the organisation and potentially cost a lot of money.

If there is reasonable suspicion that the incident was triggered by an insider: then using computer forensics may be the right route to take. If this is the case consider the use of a specialist dedicated computer forensics team that are experienced at providing expert-witness.

Taking forensic images is no longer the standard approach taken for cyber incident response and it is rarely beneficial.

5. Make sure the response is less damaging than the incident

Rebuilds are often undertaken “to be safe”, even though the technical need for this is rare. This causes downtime and increases cost. If a rebuild takes place before the incident is analysed, it could result in critical evidence of attacker-activity being destroyed.

It is difficult to respond to a situation that is not understood unless an organisation is lucky. Relying on luck is rarely a good strategy.

There are cases of organisations switching off Internet connectivity, powering down server racks and shutting down critical systems. Whilst there may be a few catastrophic scenarios where this is the right thing to do: this is incredibly disruptive to an organisation and more often than not a panic-response. Make sure that the post incident assessment considers the disruption versus the risk to determine whether the response was reasonable and proportionate. Every incident is a learning opportunity.

Finally

There is no such thing as “perfect-defence”. Many organisations will deal with cybersecurity incidents at some point and the costs associated with data-breaches is reported as averaging millions of pounds. As an incident may involve PR and legal experts as well as the cyber incident specialists: costs can mount quickly. The decision-maker can play a key role in ensuring the right business outcomes are achieved.

An introduction to cybersecurity for decision-makers

Cybersecurity is an industry, a field of academia, a buzz-word, a science, an art and a bogeyman. And whilst cybersecurity cannot be avoided within any organisation that relies upon computers and data: there needs to be a way by which senior decision-makers can be involved in, and make decisions on, cybersecurity matters.

Cybersecurity is a highly specialised subject. It is complex and requires significant of knowledge and experience that is different from normal IT-knowledge. Knowing jargon and buzzwords does not mean that someone is an expert so always check the credentials of your “trusted advisors”.

Despite its overuse as a term, cybersecurity is fundamentally about protecting computer systems and data.

There are rules

Most territories now have laws around Data Privacy and many industries have regulations around information security. These must always be complied with and, irrespective of whether they are useful, they are necessary to operate in specific sectors.

Whilst the regulatory requirements may originate from the best of intentions: it is likely that organisations will need to do additional things to have the right type of cybersecurity for their specific profile and operations.

Why does anyone need cybersecurity?

Questioning why cybersecurity is needed is a good starting-point as it helps anchor solutions and initiatives to the fundamental driver behind activity in this space.

- The more you rely on (take advantage of) IT, therefore

- The bigger an impact to the organisation if something goes wrong, therefore

- The more you need cybersecurity

Cybersecurity needs to be seen as an enabler to using IT. Without cybersecurity, reliance upon IT is an incredibly risky thing to do. In-fact, one of the oldest risk equations in InfoSec (Information Security) works as follows:

Threat[1] x Impact[2] x Opportunity (Vulnerability)[3] = RISK

In mathematics if anything is multiplied by zero then the answer is zero. If there were no Threats there would be no Risk. If there was no Impact there would be no Risk and if there was no Opportunity to compromise a system there would be no Risk.

There are formal methodologies to measure the level of risk to an organisation as a result of a computer security breach. Sometimes formal assessments are useful to help shine a light on the scale of the issue. But if you are not required to undertake them then, in most cases, there is little benefit in going down this route.

Cybersecurity is a cost and, like other costs, it should be managed. For many organisations this means that the goal is to spend as little as possible on cybersecurity whilst having a proportionate level of protection considering the risk. Getting that proportionality right can be a challenge. Cybersecurity is routinely both a victim to underspending, where there is a lack of appreciation of the subject, and a cause of overspending, where the expenditure has not been objective focussed and consequently failed to achieve a useful outcome.

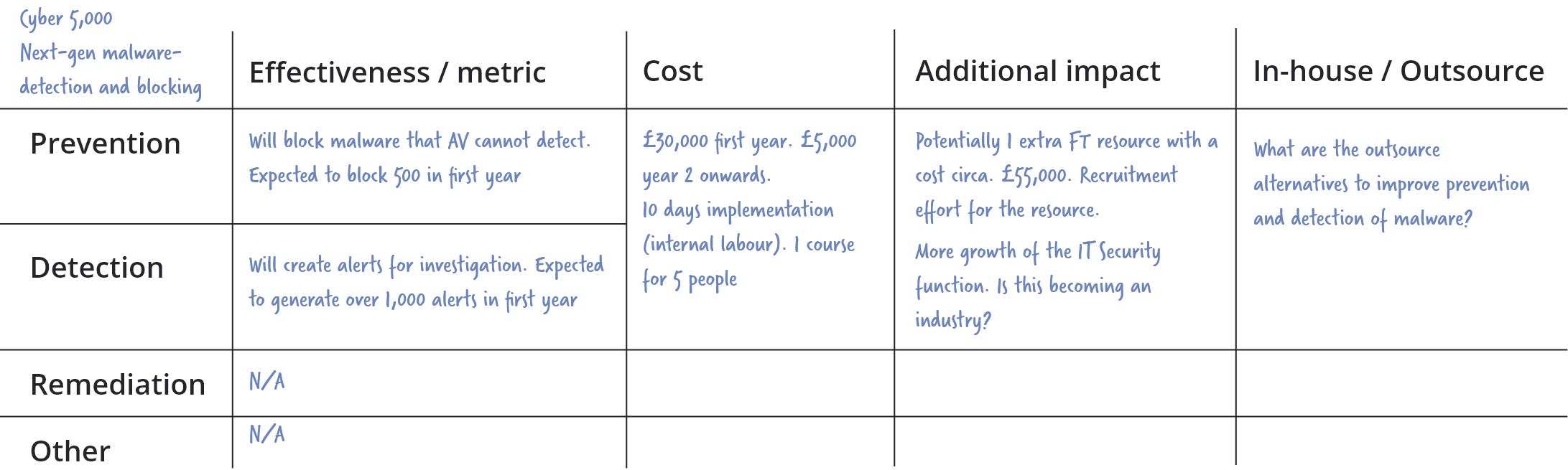

There are three fundamentals that an organisation needs to do regarding cybersecurity:

- Prevent an incident from occurring[4] – not all incidents can be prevented

- Detect an incident that has occurred – anti-virus cannot detect all incidents

- Respond well to an incident that has occurred – a good response can negate the impact of an incident

There may be exceptions to the above; but in-general all cybersecurity expenditure should be aligned to at least one of those three. Therefore, mapping initiatives against them can be a useful activity. Combining this with an articulation of effectiveness (a metric is best) is useful as it helps focus the initiative on the right outcomes for the organisation. At the risk of repetition: remember that cybersecurity is highly specialised. It requires specialist tools in the hands of specialist practitioners. Whilst an organisation could build their own Security Operations Centre (SOC), the question of “why?” should be raised. A company could generate its own electricity: but why would it do so?

Cyber expenditure almost always consists of both:

- Anticipated expenditure – the cost of the tool, service or technology

- Additional impact – specialist and (or) additional people, extra-training, recruitment, facilities and a distraction from core business

The following matrix (with a made-up example) is provided to help characterise cybersecurity initiatives. It is intended to be completed quickly, on the back of a post-it note, to help rapidly focus attention on the nature of the investment and whether the benefit, costs and approach have been considered. It is not intended to replace a full-investment case.

Final notes

No matter how much is spent on cybersecurity, and no matter what you are told, no company or product can guarantee safety. All anyone can do is make it less likely that an organisation will be compromised or reduce the impact of compromise. The inverse, i.e. not spending any money on cybersecurity, does not guarantee that an organisation will suffer a security breach. Not every organisation gets hit and some organisations are lucky. However, a strategy requiring luck is not recommended.

Whilst cybersecurity should be on the agenda: it should not monopolise it. Cybersecurity should be frictionless and, ideally, left to the professionals who should take the pain of it away. If cybersecurity is routinely causing you pain it is worth asking whether it is being managed as well as it could be.

Footnotes

[1] “Threat” refers to the groups or persons who do the attacking: Hackers, Nation States, Hacktivists. The entities that undertake the attack.

[2] Impact is not just the confidentiality breach of information. Depending on the circumstances, availability or integrity compromises can be highly impactful.

“Impact” is the impact to your organisation if they succeed in stealing, destroying, changing or making your systems and data unavailable.

[3] “Opportunity (Vulnerability)” is a measure of how accessible the systems and data are to attackers. Very secure government systems are not directly connected to the Internet and this reduces the Opportunity of attack considerably.

[4] Attackers have access to all the same technology that the defenders have and despite the prevalence of firewalls and anti-virus (both of which are much needed by the way), they are still able to breach organisations security and gain access to systems and data. Prevention is better than cure, but it’s just not practical to rely solely on this element.

Most popular posts

1. Four questions you need to answer after a cyber attack

2. Top 3 reasons the education sector is a prime target for cyber attacks

3. An introduction to cybersecurity for decision-makers

4. Cyber Incident Response for decision-makers

5. Law firms and cyber crime; the growing threat to the UK legal sector